In the Restorative Justice program, residents hand-make textile products for children on the autism spectrum and the elderly while healing themselves within

Story by Marcus Wilkins

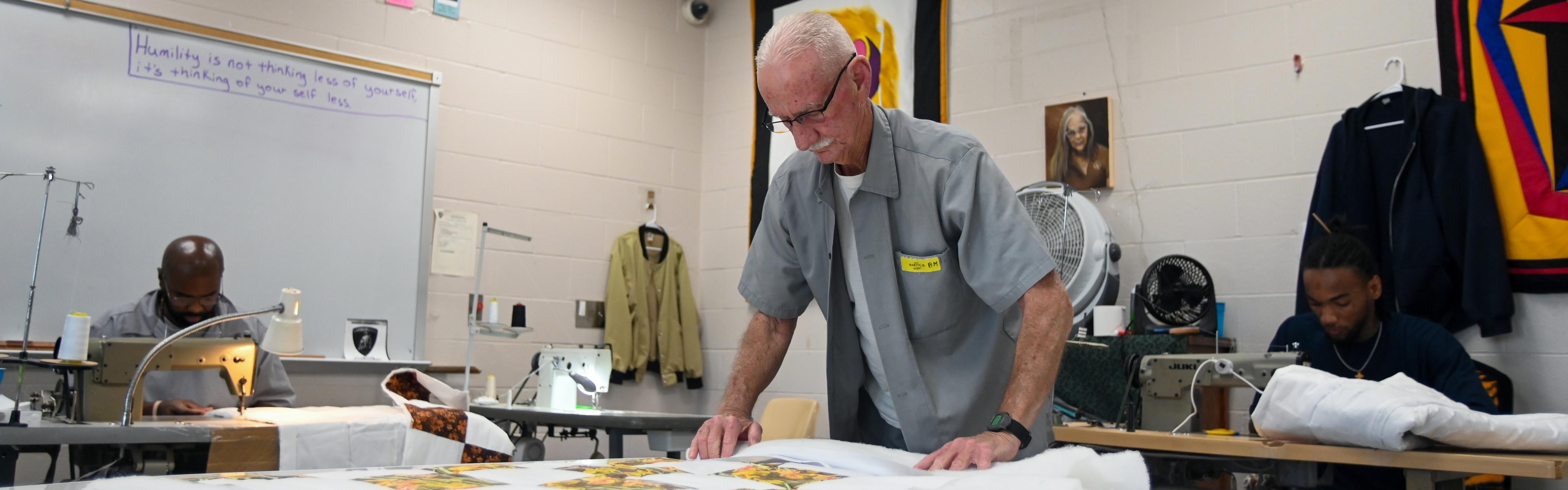

Timmy Jackson smooths the ragged seams of fabric spread on the table in front of him. The hodgepodge quilted layers are tattered and unfinished at the moment, providing a glimpse into a painstaking process dependent on discipline, focus and cooperation.

Here in the Restorative Justice (RJ) sewing room at Jefferson City Correctional Center (JCCC), the blanket — made from reclaimed material reimagined as something beautiful and new — is a tangible metaphor for a collective commitment to personal transformation.

Jackson, who is serving a life sentence, is demonstrating the steps that go into making a weighted blanket that will eventually soothe a Missouri child on the autism spectrum.

“We started folding it inside out to hide the stitching so it won’t fray as much,” said Jackson, one of the sewing room’s two lead quiltmakers. “We’ve been trying to make it neater because when you used to open it, there would be raw ends and the blankets would unravel.”

The RJ program was established in 1997 with the goal of giving back to Missourians through nonprofit agencies. It’s an idea that received national attention this year from the Netflix documentary The Quilters, about South Central Correctional Center (SCCC) residents at who create quilts for foster children in Texas County.

Other initiatives include RJ gardens, cultivated by residents to provide fresh produce to local food banks; Puppies for Parole, through which residents train and socialize thousands of rescue dogs for adoption; and several workshops that transform donated raw material into handmade goods.

“Seeing the joy these bring to kids is special,” said Scott Barmore, who is serving a 30-year sentence. “To restore justice, to give back and maybe start to make amends for a lot of the things I did in my lifetime — that’s what it’s all about. This is an extension of that understanding.”

In addition to the weighted blankets, the RJ sewing shop produces fidget blankets with beads and textures to calm Alzheimer’s patients in nursing homes. The shop has partnered with district attorneys’ offices to provide blankets to children who must take the witness stand, providing some comfort when they’re confronting their abusers in court. The team also makes wall tapestries, featuring comic book superheroes, and stuffed animals — known as RJ Buddies — with weighted, dangling arms that provide neurodivergent children with comforting hugs.

Residents who work in the sewing room must also participate in mandatory Impact of Crime on Victims classes. The 13-week curriculum invites victims to a safe and structured environment to talk about the impact of crime on their lives. Classes help residents develop sensitivity and prevent further victimization.

“A victim is someone who didn’t have a choice in the matter,” said Steven Green, the other sewing room lead. “Growing up — stealing, cussing people out, doing whatever to people who didn’t do anything to me — those are all victims. I’m through with all that. To me, ‘restore’ means to make new again, or maybe even better than before.”

Therapeutic Thread

In many ways, Lily Motley is a typical 9-year-old girl. She loves animals and visiting the zoo. She plays with — and occasionally squabbles with — her 10-year-old sister, Annabella. She loves spending time with her family.

Lily also has level-three autism, the most severe form, meaning she is nonverbal and requires constant care. When the Motleys discovered Central Connections, a nonprofit case-management agency that provides resources to families of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, it was a godsend.

Through its partnership with the Missouri Department of Corrections, the agency delivered to Lily what would become her favorite blanket.

“Lily gets upset easily, but when she has her weighted blanket, she calms down instantly,” said Lily’s mother, Lottie. “It goes with her everywhere, and we even ordered another one from the DOC because she loves it so much.”

Weighted blankets provide deep-pressure stimulation, which helps activate the parasympathetic nervous system to reduce anxiety. This calming effect can be especially beneficial for children on the autism spectrum or individuals with mental health issues by improving sensory regulation and emotional stability.

As orders come into the RJ sewing room, the team moves with a unified purpose to fill them. Sometimes requests are specific — blankets embroidered with Sonic the Hedgehog, Barbie or Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Other times the crew is free to improvise and creatively cobble together whatever swatches they’re inspired to use. Each team member is qualified to perform every stage of production — from design layout to cross-stitching to finishing seams.

“One time we recreated an entire page, frame by frame, of a Spider-Man comic book,” said Jackson. “There’s nothing we won’t try to make. You name it, we’ll figure it out and deliver it.”

Robert Martin, the group’s elder statesman at age 78, works with a craftsman’s dexterity pinning and ironing fabric before passing it along to a teammate who will begin stitching.

“I’ve served 43 years of a mandatory 50-year sentence, and I’ve probably sewed for 25 years of it,” said Martin, who previously worked in the JCCC Missouri Vocational Enterprises warehouse making officers’ uniforms. “It’s meditative, therapeutic and relaxing. It takes your mind off things.”

Sewn to Heal

Kevin Yancey sees human potential everywhere. A devout Christian who believes God has provided him with a path to help residents heal and succeed, he now works in the Reentry Center — literally connecting men to their futures. It’s his latest gig in 12 years with the department.

Yancey started as a corrections officer, but after witnessing the impact of a treatment program during his first assignment at Fulton Reception and Diagnostic Center, he went back to school to advance his career.

“Witnessing treatment’s positive impact really inspired me, and I knew I wanted to be a part of it,” said Yancey, who served as director of the JCCC RJ Program 2018–24. “My passion for restorative justice has been seeing the transformation of guys signing up for classes. When they come in, you can see there’s a fire in their eyes and that they really want to change. The best way to describe them is diamonds in the rough.”

To help polish those diamonds, the RJ Program relies on its inherent network of support and accountability — a brotherhood, so to speak.

“The camaraderie in restorative justice runs pretty deep,” Jackson said. “This organization is like my family, and we all know about everyone’s family on the outside.

“We have to be able to trust one another, to hold everyone accountable and to communicate. If the communication is shut down, then everything gets shut down and we can’t accomplish our goals.”

As with any workplace, over the decades, the sewing room has experienced many collective moods and moments. The men have laughed, argued, celebrated, grieved, healed — all while producing several thousands of handmade items for Missourians in need.

With each stitch in time, the team continues to mend and restore.

“At one point, making fidget blankets for witnesses, I had to make 100, and to some people that might be grueling,” Green said. “But I don’t see it that way. These are for someone who is hurting. Someone who needs it. As I do this work, I think about my goal — to be better tomorrow than I am today.”